By Rota Rulle

•

January 30, 2026

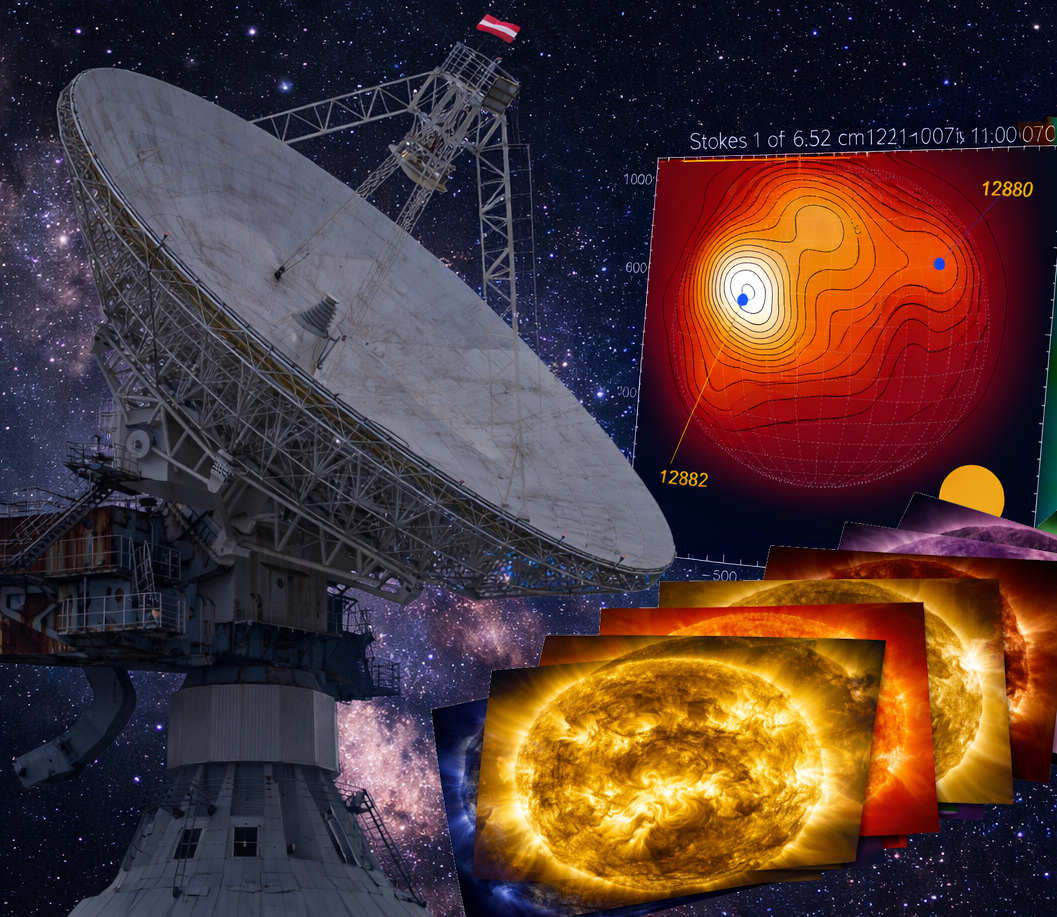

Advanced Diagnostics of Solar and Stellar Flares: STEF Project Successfully Concludes with Lasting Scientific Impact An international research team based at the Ventspils International Radio Astronomy Centre (VIRAC) , Ventspils University of Applied Sciences, has successfully completed the Latvian Science Council–funded project “Multi-wavelength Study of Quasi-Periodic Pulsations in Solar and Stellar Flares (STEF)” (No. lzp-2022/1-0017) . The project has delivered major advances in solar and stellar physics, radio astronomy methodology, and time-domain astrophysics, while establishing a strong foundation for continued international research. Key scientific and technical achievements Over its three-year duration, STEF produced a coherent, high-impact body of results , including 17 peer-reviewed publications in Q1–Q2 international journals , addressing one of the central challenges of modern solar physics: understanding how magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) waves and oscillations modulate energy release in solar and stellar flares. The project significantly advanced: Theoretical modelling of MHD waves , including the effects of thermal misbalance, non-local thermal transport, and boundary conditions on wave damping, persistence, and amplification. Observational diagnostics of quasi-periodic pulsations (QPPs) in solar and stellar flares, strengthening their interpretation as wave-driven phenomena. Helio and asteroseismology , extending oscillation-based magnetic diagnostics from the Sun to solar-like stars. Time-domain radio astronomy , through validated single-dish and interferometric methodologies developed at the Irbene observatory. Observational infrastructure, datasets, and software A major strength of STEF was the integration of theory with instrumentation and data analysis. The project established routine microwave solar observations with the RT-32 radio telescope , producing a curated solar radio observation dataset that includes full-disk mapping and long-term monitoring of individual active regions in multiple frequency bands and circular polarisations. This dataset provides a valuable observational basis for future studies of solar activity, flare precursors, and oscillatory phenomena. In parallel, the project advanced single-baseline interferometric techniques (RT-32–RT-16) for detecting faint, short-lived radio variability associated with stellar flares. To support these studies, the team developed and released an open-source interferometric/VLBI visualisation and inspection tool , enabling interactive time–frequency exploration, rapid identification of radio-frequency interference, and validation of transient candidates in long, high-cadence datasets. In addition, the Warwick project team released the SCOPE software package for statistically robust detection of oscillatory signals using empirical mode decomposition, applicable across astrophysics and other data-intensive disciplines. International collaboration and continuity STEF was embedded in a broad international network, with active collaboration involving observatories and universities across Europe. A strategic partnership with the University of Warwick (United Kingdom) played a central role, including invited lectures, joint workshops, and close interaction between theory, observations, and advanced signal analysis. Although the STEF project has formally concluded, its scientific programme continues and expands . Several new funded projects launched in 2025–2026 directly build on STEF results, ensuring the long-term sustainability of the developed methodologies, software, and international collaborations. References list: Arregui I., Kolotkov D.Y., Nakariakov V. M., "Bayesian evidence for two slow-wave damping models in hot coronal loops", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 677, art. no. A23., 2023, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202346834 Belov S. A., Goffrey T., Arber T. D., Kolotkov D. Y., “ Non-Local Thermal Transport Impact on Compressive Waves in Two-Temperature Coronal Loops”, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 693, art. no. A186, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202452938 Belov S. A., Kolotkov D. Y., Nakariakov V. M., Broomhall A. M., “Detecting Quasiperiodic Pulsations in Solar and Stellar Flares with a Neural Network”, The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, ApJS 274 31, 2024, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4365/ad6f98 Belov S.A., Riashchikov D.I., Kolotkov D.Y., Farahani S.V., Molevich N.E., Bezrukovs V., ”On collective nature of non-linear torsional Alfvén waves”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 523 (1), pp. 1464 - 1473, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad1480 Berloff N. G., Broomhall A. M., Hookway G. T. , Lund M. N., Millson L. J., Kolotkov D., “Investigating magnetic activity cycles in solar-like oscillators using asteroseismic data from the K2 mission”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 546 (3), 2026, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stag092 Bezrukovs D., "Microwave observations of the Sun in Virac: An experience of implementation", Sun and Geosphere, vol.15, issue 2, pp.55-58, ISSN 1819-0839, 2023, http://dx.doi.org/10.31401/sungeo.2022.02.02 Bezrukovs V., et. al., “Effects of the Intraday Variability of the Radio Galaxy Perseus A (3C 84) at a Frequency of 6.5 GHz and Evidence for a Possible FRB Event”, Galaxies, 14(1), 1, 2026, https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies14010001 Cho K.-S., Kolotkov D. Y., Cho I.-H., Nakariakov V. M., “Frequency-dependent Evolution of Propagating Intensity Disturbances in Polar Plumes”, The Astrophysical Journal, ApJ 992 33, 2025, https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/adfde0 Hejazi S. M., Van Doorsselaere T., Sadeghi M., Kolotkov D.Y., Hermans J., “The effect of thermal misbalance on magnetohydrodynamic modes in coronal magnetic cylinders”, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 694, art. no. A278, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202450731 Kolotkov D. Y., Broomhall A. M., Hasanzadeh A., “Effects of the photospheric cut-off on the p-mode frequency stability”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 533 (3), pp. 3387–3394, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stae2015 Kolotkov D.Y., Nakariakov V.M., Cloesen M., “The centroid speed as a characteristic of the group speed of solar coronal fast magnetoacoustic wave trains”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 527 (3), pp. 6807 – 6813, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad3681 Lim D.,Van Doorsselaere T., Nakariakov V. M., Kolotkov D.Y., Gao Y., Berghmans D., “Undersampling effects on observed periods of coronal oscillations”, Astronomy and Astrophysics, 690, art. no. L8, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202451684 Meadowcroft R.L., Zhong S., Kolotkov D.Y., Nakariakov V. M., “Observation of a propagating slow magnetoacoustic wave in a coronal plasma fan with SDO/AIA and SolO/EUI”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 527 (3), pp. 5302 – 5310., 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad3506 Nakariakov V. M., Zhong S., Kolotkov D.Y., Meadowcroft R.L., Zhong Y., Yuan D., “Diagnostics of the solar coronal plasmas by magnetohydrodynamic waves: magnetohydrodynamic seismology”, Reviews of Modern Plasma Physics, 8 (1), art. no. 19., 2024, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41614-024-00160-9 Nakariakov V. M., Zhong Y., Kolotkov D.Y., “Transition from decaying to decayless kink oscillations of solar coronal loops”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 531 (4), pp. 4611 – 4618., 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stae1483 Zhong Y., Kolotkov D.Y., Zhong S., Nakariakov V. M., "Comparison of damping models for kink oscillations of coronal loops", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 525 (4), pp. 5033 - 5040, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad2598 Zhong S., Nakariakov V. M., Kolotkov D. Y., “A 50-Minute Coronal Kink Oscillation and Its Photospheric Counterpart”,The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 993 (L35), 2025, https://doi.org/10.3847/2041-8213/ae122e Zhong S., Nakariakov V.M., Kolotkov D.Y., Chitta L.P., Antolin P., Verbeeck C., Berghmans D., “Polarisation of decayless kink oscillations of solar coronal loops”, Nature Communications, 14 (1), art. no. 5298., 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-41029-8 Software list: Šteinbergs J., Visualization tool for interferometric data do standard calibration and data visualization of interfereometric data. https://github.com/VIRAC-SPACE/Visualization-tool-for-interferometric-data Kolotkov D., Python tool: scope - Statistical Confidence of Oscillatory Processes with EMD (Empirical Mode Decomposition). https://github.com/Warwick-Solar/scope This project was funded by the Latvian Science Council project “ Multi-Wavelength Study of Quasi-Periodic Pulsations in Solar and Stellar Flares (STEF)” , lzp-2022/1-0017